Pierre Fraser is an author, essayist, and (currently) a PhD candidate in sociology at Université Laval. Just as his most recent book (Tous Malades !: Quand l’obsession pour la santé nous rend fous) was being published, I met Pierre on Twitter, where we discovered our mutual interest in the subject of healthism. Pierre blogs at Pierre Fraser and tweets as @pierre_fraser.

Pierre Fraser is an author, essayist, and (currently) a PhD candidate in sociology at Université Laval. Just as his most recent book (Tous Malades !: Quand l’obsession pour la santé nous rend fous) was being published, I met Pierre on Twitter, where we discovered our mutual interest in the subject of healthism. Pierre blogs at Pierre Fraser and tweets as @pierre_fraser.

This translation would have been impossible without the invaluable assistance of Jan Henderson (PhD in the history of science and medicine from Yale). Her work allowed me to revisit the original French text and enhance it, and in this sense, we followed the injunction of Karl Popper : the duty of clarity. I hope our collaboration will continue, because Jan and I are particularly concerned about the healthization of society, and we try to understand how health has become a social value. Feel free to send us your comments (Jan Henderson, Pierre Fraser).

Pierre Fraser, 2012

When a medical clinician examines a patient, she first determines the presenting symptoms, considers which bodily functions might account for those symptoms, arrives at a diagnosis, and provides the most appropriate treatment. But what if the presenting symptom is depression? As Alain Ehrenberg points out, “depression, like any mental illness, is not a disease that can be assigned to a part of the body.” [1] In fact, as Ehrenberg goes on to say: “when psychiatry can discover the cause of a mental illness, as happened with epilepsy, it is no longer a mental illness.” [2] Such has been the dilemma of the history of psychiatry.

Consider, though, what has happened in the history of depression. Seventy years ago an individual who suffered from depression was considered sick, but curable. Today our assessment is that such an individual has a chronic disease. [3] How can we explain this historical progression?

When we look closely at the history of psychiatry it teaches us one thing very well: “disagreements about the causes, definitions and treatment of diseases, as well as the uncertainties that have accompanied the history of psychiatric reasoning, are particularly revealing about the transformation of the individual.” [4] Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, our concept of the individual has undergone fundamental transformations. Given that we now hold “the gospel of personal development in one hand and the cult of performance in the other” [5], we can see that “the history of depression reveals how the type of person we have become has followed in the wake of demands for psychic emancipation and individual initiative. What insanity is to reason and neurosis is to conflict, depression is to insufficiency.” [6] Emancipation and empowerment bring the expectation that the individual will perform. But will that performance be adequate? Depression is the result of feeling that our life’s performance is not sufficient.

A social bond in crisis

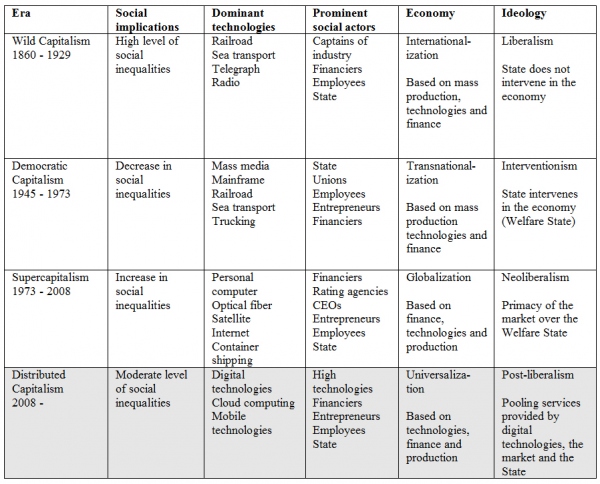

The Age of Wild Capitalism (1860-1929) was dominated by the captains of industry. Private enterprise reigned supreme and regard for the individual was at the same level as regard for commercial merchandise. This was followed by the Age of Democratic Capitalism (1930-1973), when the state, in response to the Great Depression, began to intervene in markets by imposing regulations. The Age of Supercapitalism (1973-2005) began with the first oil crisis. The economic difficulties of the era created an opportunity for President Ronald Reagan and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher to deregulate a variety of economic sectors. The period culminated with globalization. Finally, I would like to propose that we are now in an Age of Distributed Capitalism [9] where the dominant influence will be high-tech industries. This stage will enable the complete empowerment of individuals: they will be fully in charge of their lives through the use of inexpensive and widely available technologies.

In this table what stands out first and foremost is a correlation between the dominant ideology of each era and the relative hierarchy of the players. In the Age of Democratic Capitalism, the state is the most prominent social actor. Entrepreneurs and financiers are relegated to the bottom of the scale. This is a complete reversal of the positions they held in the previous age. The reversal is apparent not only in the rise of unions, but in the implementation of major social protection programs that are characteristic of this age. Though these programs took on different forms in different countries, the intention was the same. We see here an example of what Durkheim called ‘organic solidarity’: a social cohesiveness and interdependence that arises from the division of labor. This state of affairs allows individuals to benefit from the basic protections of society while feeling their contributions are valued as useful. [10]

On the grammar of depression

The Age of Democratic Capitalism appears, at first glance, to be highly favorable for the individual. Thanks to various social measures, it was a time when the state offered increased protections against life’s misfortunes. Living conditions improved for all economic classes. Purchasing power increased annually, and “those born after 1945 not only have the best physical health in modern history, but have also been raised in a period of unprecedented prosperity.” [11]

It might seem paradoxical that the prevalence of depression would increase in this era, but this was definitely the case. In 1989, the American Medical Association published a summary of epidemiological studies of depression and concluded: “the increased risk of depression for those born after the Second World War is indisputable.” [12] There had been an astonishing amount of material progress, yes, but this was accompanied by “urbanization, geographic mobility, emotional breakdowns, the growth of social anomie, changes in family structures, and the embrittlement of gender roles.” What is especially interesting about the epidemiological studies is that they all converge on the same explanation for the rise of depression: social change.

We must admit that social change alone cannot explain everything about depression. There must also be a ‘grammar of depression’ through which individuals may conduct their own diagnoses, and this grammar can only exist if depression is institutionalized. Around 1960 “anxiety, insomnia and overwork as the themes of depression appear publically in major magazines.” [13] They provide “an interpretive tool to solve or overcome intimate problems.” [14] In other words, depression involves actors who supply the hows and whys of their problems, while mass media tell people how to deal with those problems. Depression is thus “produced in a collective construction that provides it with a social framework in which it exists.” [15] Depression becomes a social reality and a “grammar of the inner life for everyone.” [16] Once individuals understand that they are subject to depression, however, there is a social crisis. If individuals regard themselves as depressed, will they be able to perform the roles expected of them by society? A society functions best when its members feel that what they are doing is useful. Depression, with its sense of the insufficiency of the individual, calls this into question. A society needs motivated, mentally healthy citizens, but will it be able to alleviate the widespread incidence of depression?

As Alain Ehrenberg has emphasized, “democratic modernity — this is its power — has gradually turned us into men who have nothing other than our own selves to guide us. We are gradually put into a position where we have to make our own judgments and create our own standards.” [17] The possibility of living our lives as sovereign, autonomous individuals has not only become a reality for some of us, as anticipated by Nietzsche, but is now the common reality for everyone. In times past, an individual who did not respect the rules (what is permitted/prohibited) was seen as guilty of a ‘sin.’ Today, however, he is blamed for a ‘failure of responsibility’ (what is ‘possible/impossible’). The individual can no longer agree to accept the label ‘guilty’ without giving it much thought. The sovereign individual must feel the weight of responsibility for his actions. This reconfiguration of the individual self brings us back to the contemporary prevalence of depression. As Ehrenberg points out, depression is now something intrinsic to the individual: “it is the failure of internal resources.” [18]

About depression

It is quite possible that depression is an anomic condition (Durkheim). That is, it occurs in contexts where the individual, confronted with the duality “possible/impossible,” feels he must “be himself,” but he lacks the “instructions” for how to accomplish this. We are no longer expected to conform to an obvious discipline. We are required to “be ourselves.” Depression, as Durkheim suggests in connection with suicide, arises from the “malady of infinite aspiration,” where everything seems possible, but in fact, nothing is possible.

To answer the basic question with which I began — whether there is a causal link between depression and the increasing empowerment of the individual — it seems plausible to say yes, given that “projects, motivation, and communication are now norms that dominate our culture.” [19] “Depression becomes, so to speak, how the individual safeguards himself. It acts as a kind of counterpart to all the energy that must be exerted simply to maintain the self as sovereign.” [20]

© Pierre Fraser & Jan Henderson, 2012

[1] Ehrenberg Alain, La fatigue d’être soi, dépression et société, Odile Jacob (poches), Paris, 2000, p. 21.

[2] Idem, p. 22.

[3] Idem, p. 251.

[4] Idem, p. 22.

[5] Idem, p. 255.

[6] Ibidem.

[7] I designed this table in 2009 — to gain an overview of the historical eras — when I co-authored the book “Les imbéciles ont pris le pouvoir, ils iront jusqu’au bout !” Published by “Near Future.”

[8] Krugman Paul, L’Amérique que nous voulons, Flammarion, Paris, 2008, p. 352.

[9] This is currently a speculative proposition that must be supported by empirical evidence from current trends.

[10] Durkheim Émile, De la division du travail social, eBooksLib on iBookStore, iPad version, p. 377.

[11] Ehrenberg, 2000, p. 142.

[12] Ibidem.

[13] Idem, p.143.

[14] Ibidem.

[15] Ibidem.

[16] Idem, p. 145.

[17] Idem, p. 15.

[18] Idem, p. 177.

[19] Ibidem.

[20] Hadler Nortin M., Malades d’inquiétude ?, translated from English by Fernand Turcotte, MD, Québec, PUL, 2010, p. 1.

I was gripped by the subject but taken aback by the some of the propositions.

The myth that technology will empower us was powerfully examined in a recent series called All Watched over By Machines of Loving Grace by Adam Curtis. He traced the origins of this technologism back to the founders of personal computing and neoliberalism. You can watch it on line. Slavoj Zizek also pokes fun at the idea in an article for the LRB http://www.lrb.co.uk/v25/n10/slavoj-zizek/bring-me-my-philips-mental-jacket

In the UK only about 25% of adults possess smartphones, and though this is likely to rise, what they (and their users) will be able to do with them depends ultimately on your ability to compete in a consumer world; the money in your pocket, your knowledge, social contacts, etc.

The rise in depression is driven in part by a rarely criticised assumption that happiness equals health, just as a beautiful body is a healthy body, and low sexual desire is unhealthy.

Where I agree with you is that depression is related to anomie. This is particulary noticeable in my immigrant Kurdish patients, predominantly middle aged from rural farming communities, in East London they lack their social roles and present with ‘impossible to treat’ symptoms of depression and somatisation. Group therapy seems to be making some progress, but they are heavy users of NHS resources.

I will conclude with another criticsim I am afraid; a quote from Richard Sennett: “The reigning myth today is that the evils of society can all be

understood as evils

of impersonality, alienation, and coldness. The sum of these three is

an ideology

of intimacy that transmutes political categories into psychological categories.”

Richard Sennett, The Fall of Public Man

Jonathon

Dear Jonathon,

I must admit it was too premature to talk about Distributed Capitalism. This is a hypothesis that I have not checked yet, but still a central concern of my dissertation. And as I can see, it has disturbed you from the main subject : causal relationship between empowerment and depression. I apologize…

But in a near future, maybe in march or april, I will post an article (tentative theory) on my blog about this phenomenon that is gaining ground, even if we want it or not.

I have really appreciated your comment, and be sure I will keep an eye on your futur comments about it !

Best regards,

Pierre Fraser

Hi Pierre,

Really interesting reading this.

I would like to add a few to all the named factors that cause depression if you dont mind :-)

Most of the population nowadays live in the crowded urban areas where is easy to get so detached from the cycles of nature, like seasons or day/night. We can do anything at any time, eating grapefruits in the cold winter, work night shifts, and not even hesitate that it would be something strange… Well, we have a technology for that (not saying that is only bad!) I just mean that things are mixed up, and despite it may seem that we are ok with tropical friuts in the winter and sleeping during the day (I chose these examples for a demonstration), a human body is not designed for it or certainly we did not adapt fully yet – it has been too short time (evolutionary)…

Also, people dont move enough, and I dont mean gym only, just mean being active in general.

And then all the negative wibe from media certainly affect people too – living in the fear, anxiety etc.

Ah, there would be much more to mention but I stop it now :-)

Anyway, thanks for sharing your work!

Clare

Hi Clare,

You are right ! Everything you have mentionned contributes to the fact that the individual, confronted with the duality “possible/impossible”, feels he must “be himself,” but he lacks the “instructions” for how to accomplish this. We must never forget that depression is not only an individual matter, it’s primarily a social construction.

Thank you for your enlightening comment !

Depression takes place when you are not able to tell your feelings to anyone. For a relaxed and stress free life try to come up with the things. There is a saying that “more you know about the problem, the better you will be able to fight it”. When you know the problem you solve that half.

Hi Pierre,

That is a very interesting perspective and offers a lot of food for thought. It seems that you are viewing depression as an individual issue caused by societal construction and that may be the case for some people with some forms of depression but certainly not all or perhaps not even a high percentage. Could it be that depression has seemed to become more prevalent (which that in and of itself is debatable) not because of increased choices of the individual but rather due to an increase in the openness of society in general as society has ‘progressed’ so that discussion of depression and other mental illnesses is allowed/encouraged and the reduction of the stigma associated with depression has lessened over time as society has become more open?

Again, very thought provoking article.

Hi Ellen,

First, thank you for your comment about the fact that this is an article that provokes and makes you think. But, without the precious help of Jane, the translation of this text originally in French, would have been impossible! So be indulgent regarding the quality of English for my response to your comment!

You point to an interesting fact about the thesis I advance: the openness of society about depression. In fact, when one looks closely, it appears that if there was an opening, it is just because we have created a social category. For example, when we created the social category “Third Age” (55-79), we have created a whole industry of aging. And when we have created the social category “Fourth Age” (80+), another type of industry has set up. Whenever you create a social category, it also creates institutions, industries, practices and procedures that will govern how things are done.

In that sense, depression, as we know it today, is fundamentally a social construct inherited from the type of society we have developed. Since the seventeenth century until today, the depression was seen in different ways. Our obsessive concern about health (mental and physical) has totally changed the game. In ancient Greece, the self-concern took precedence over self-knowledge. Today, the situation is reversed. We have set aside the ethical subject in favor of an individual as a biological material. Mental suffering has become a pain that can be treated by any medicine, just as physical suffering. Sexual impotence has become erectile dysfunction. This way we treat a physical problem and not the somatic problem: social construction!

As Seneca was saying to Lucilius : “Be well !”.

I am struck by the phrase the “malady of infinite aspiration”. It seems to describe a phenomena I observe in our society, and in my own family, of young people dropping out of college the year, the semester, or weeks before they are scheduled to graduate. I think it has to do with feeling overwhelmed by the “infinite aspiration” while at the same time fearing they don’t have the internal strength to reach those aspirations. Any thoughts or observations on your part?